29/03/2024

29/03/2024Ivo Habán

The unbelievable has come true. The Prague City Gallery has expressed interest in the project of a large exhibition including visual art, photography and film, which has gone out in the covid and which I have already completely written off. After almost two years of preparation, it has now been realised in the unique space of the Municipal Library, where it will be on display until 25 August. What's more, it will continue to Slovakia in autumn 2024, where viewers will see it in a revised form of two parallel exhibitions at the Liptovska Gallery of Peter Michal Bohúň in Liptovský Mikuláš and the East Slovak Gallery in Košice. The original idea of presenting scientific research in the form of an exhibition that will present a lesser-known form of art of the former Czechoslovak space in the Czech Republic and Slovakia will be fulfilled.

The conceptual content of the exhibition is the result of the reflections of the curatorial trio (Anna Habánová, Helena Musilová, Ivo Habán). The physical form of the exhibition was further shaped by architects Richard Loskot and Rozárka Jiráková, while the graphic design was devised by Jan Havel, who was behind the monograph project. A whole team of people from the Prague City Gallery worked alongside us for several months on the actual realization, and I would like to thank them for their patience and cooperation in preparing the exhibition, as well as for the chance and trust they gave us as curators. It took a lot of effort to fill the 16 rooms of the Municipal Library with 313 carefully selected paintings, sculptures, photographs, films and projections, a bunch of plotters, an interactive map, extended captions, furniture and other items from more than 50 lenders from the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Germany.

The exhibition opened on 26 March 2024 and the opening was very emotional for me. In a quick media shortcut of mainly lifestyle shows and lists of various "bests", there was simply no space at all for some essential moments for me. But here it is. All three curators are graduates of the Brno Seminar of Art History at the Faculty of Arts of Masaryk University. I very much appreciate the fact that our teachers and, dare I say, dear colleagues, Professors Lubomír Slavíček and Alena Pomajzlová, under whose guidance we grew up and now have worked our way up to the role of curators of a major project, were present at the opening. During the opening we were also accompanied by Hana Rousová, who curated a major cross-sectional exhibition of neoclassicism in Czech art for the Prague City Gallery in 1985/1986, and in 1994 was one of the key personalities behind the now legendary exhibition Gaps in History, which for the first time presented the extinct world of parallel coexisting Czech, German and Jewish art culture of the interwar period in the Municipal Library. I had not seen either of the exhibitions; I was ten and seventeen at the time, respectively. Now I was standing in the same space with Hana Rousová, Alena Pomajzlova and Lubomír Slavíček by my side. I thank all three of them very much, for their openness, friendship and steadfast professional support, which is far from always a given in the academic world.

13/05/2021

13/05/2021Ivo Habán

The English mutation of New Realisms is complete. It was a long work and I would like to thank all those who helped me with it, especially Stephan von Pohl, Keith Holz and Jan Havel.

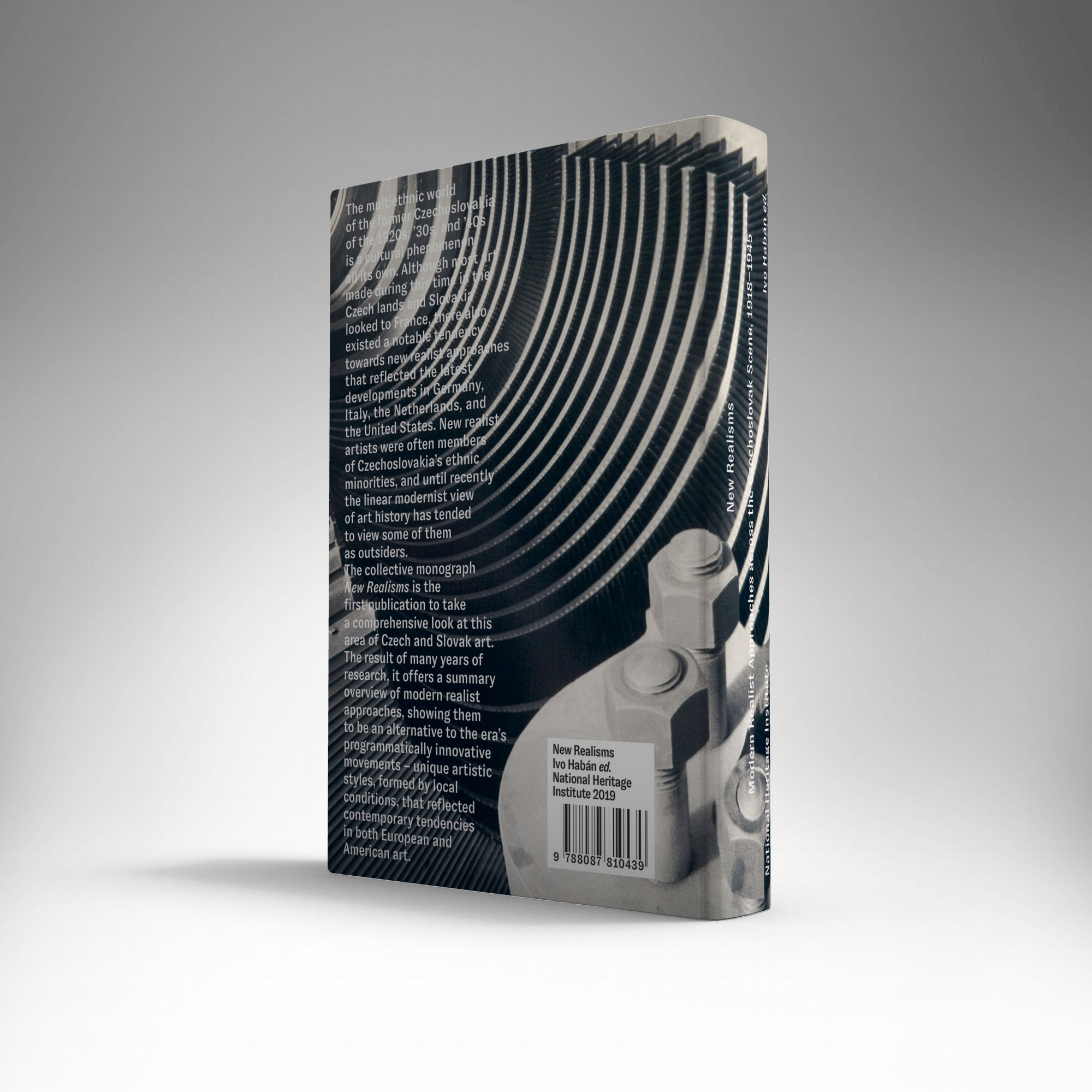

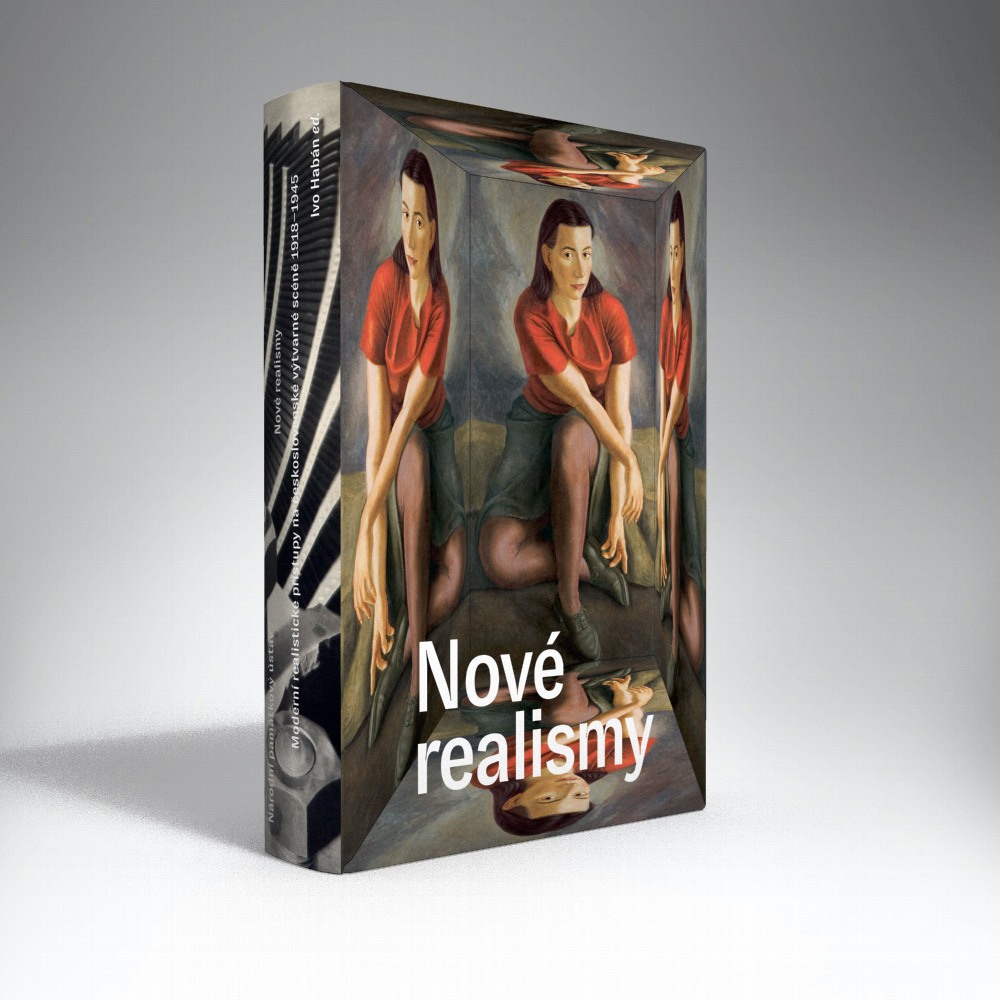

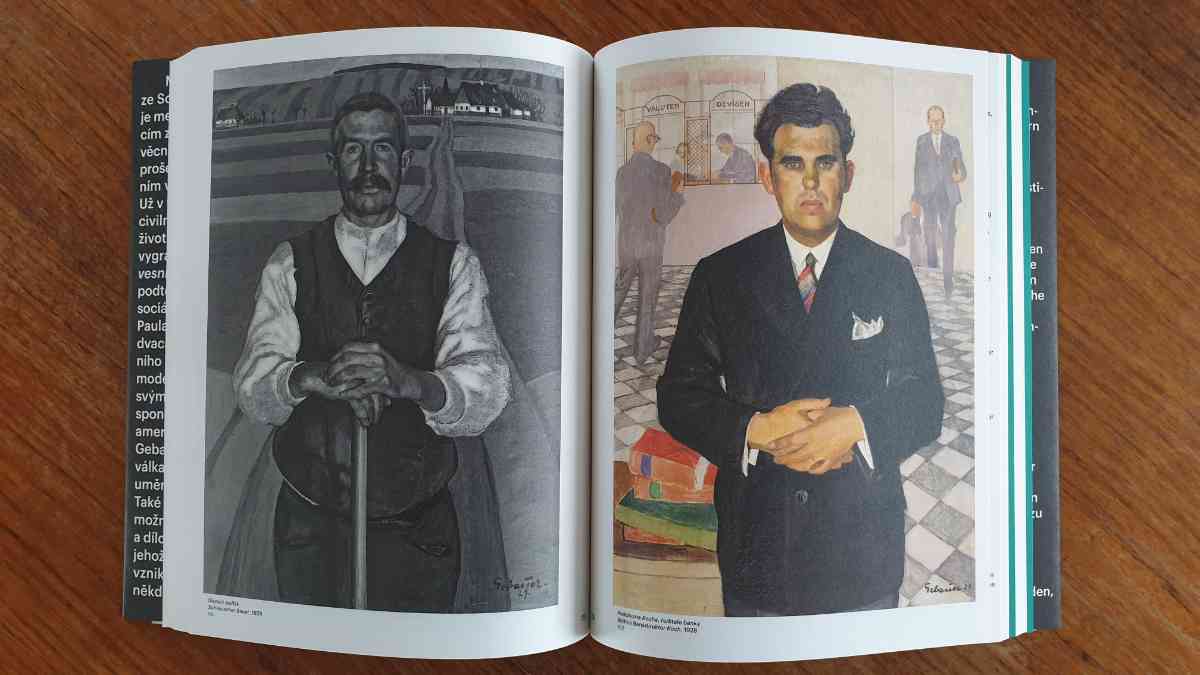

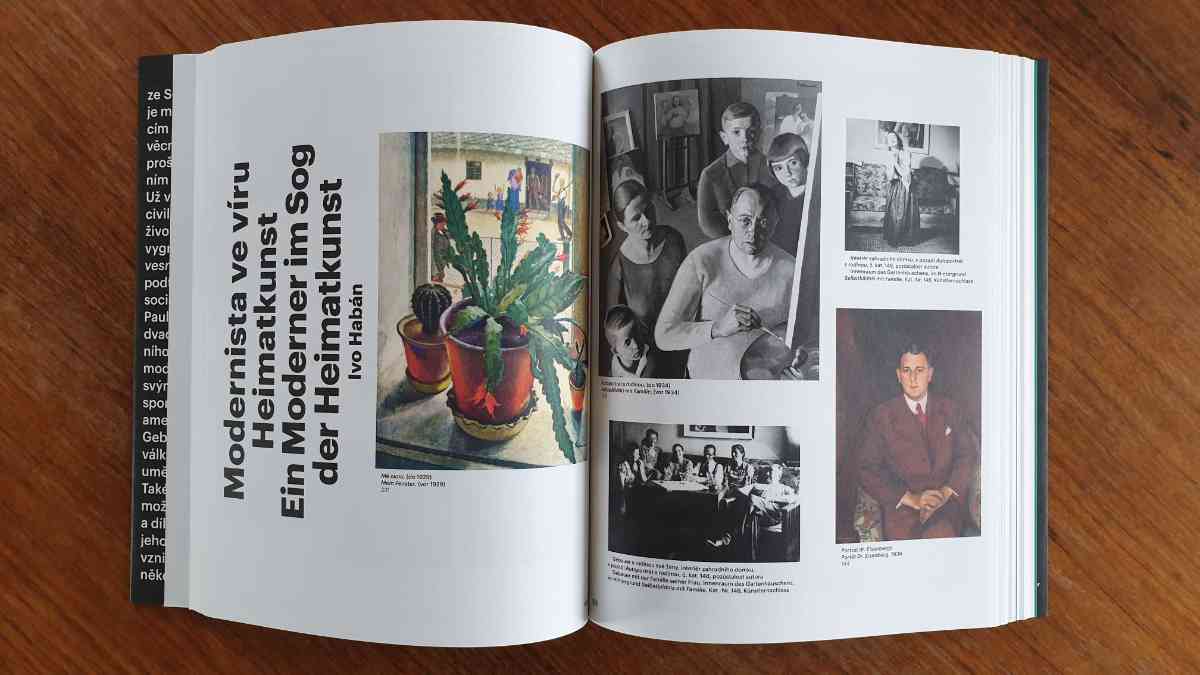

Over the course of fifteen chapters, the collective monograph New Realisms explores a subject of Czech and Slovak art history that has not previously been studied in such a comprehensive manner. The result of many years of research by a team of thirteen authors, the book offers a summary overview of modern realist approaches to art in the Czech lands and Slovakia in 1918–1945, expanded to include chapters on selected aspects of realist art before and after this timeframe, plus case studies from the related fields of film, literature, and music. Much attention has been paid to photography, a medium that contributed significantly to transforming the era’s art and its visuality. The photography of that era is often given the umbrella term “New Photography,” which shares with modern realisms a focus on modern life. In this publication, modern realist approaches are presented as an alternative to programmatically innovative tendencies – as a unique artistic style, formed by local conditions, that reflected contemporary developments abroad. Although most art made during this time in the Czech lands and Slovakia looked to France, there also existed a notable tendency towards new realist approaches that reflected the latest developments in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United States. New realist artists were often members of Czechoslovakia’s ethnic minorities, and until recently the linear modernist view of art history has tended to view some of them as outsiders.

The book traces and evaluates theoretical concepts then and now. It follows the domestic interpretation of the era’s theoretical understanding of modern realisms, defines the relevant terminology, and uses specific examples to document the specific nature of Czechoslovak art and its relationship to foreign art. Besides art labeled New Objectivity, the authors have also focused their attention on other, locally conditioned, forms of modern realism, including works by so-called “regionalists.”

—

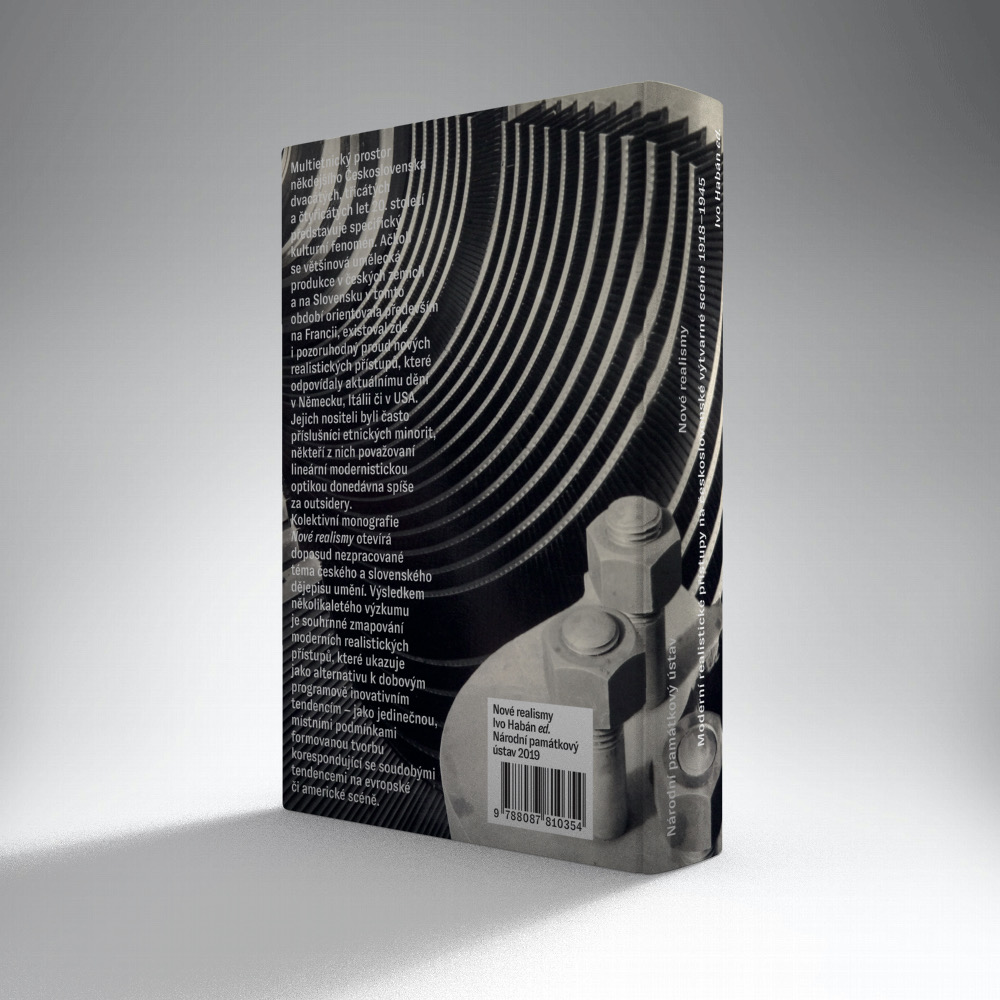

New Realisms

Modern Realist Approaches across the Czechoslovak Scene, 1918–1945

Ivo Habán (ed.), Anna Habánová, Keith Holz, Jiří Horníček, Zsófia Kiss-Szemán, Bohunka Koklesová, Barbora Kundračíková, Jana Migašová, Helena Musilová, Milan Pech, Alena Pomajzlová, Lubomír Spurný, Barbora Svobodová

Graphic design and typesetting: Belavenir

280 × 190 mm, 496 pages, 580 color and black and white reproductions

English version, German summary

National Heritage Institute, Regional Office in Liberec, 2019

ISBN 978-80-87810-43-9

Monograph in English is available on e-shop of National Heritage Institute. It is possible to buy the book in the National Heritage Institute Bookshop and information centre in the center of Prague.

10/10/2020

10/10/2020Ivo Habán

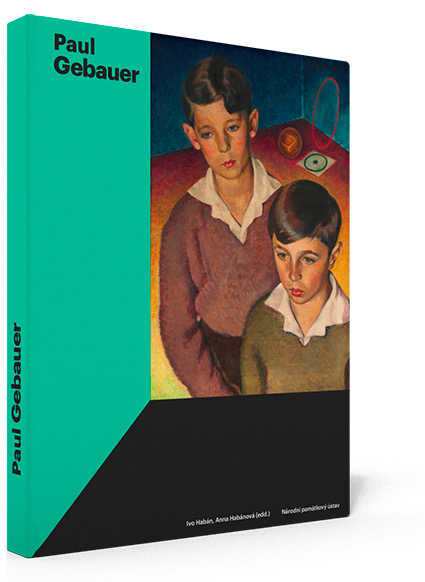

of Paul Gebauer

won Otokar-Fischer-Preis 2020

Paul Gebauer's monograph won Otokar-Fischer-Preis 2020. The monograph was created thanks to the collaboration of editors Anna Habánová and Ivo Habán with historian Branislav Dorko and art historian Lenka Valečková (Rychtářová). The book was published with the support of the The Czech Science Foundation, in cooperation with the National Heritage Institute, the Technical University of Liberec, the Silesian Museum and the Museum in Bruntál. The editors would like to thank to the members of the Paul Gebauer family, in particular Mr. Michael Gebauer and Ms. Ulrike Gebauer, who contributed significantly to its implementation, especially for their helpfulness, support and enthusiasm in making the archive materials available. Our thanks belongs also to Anna Ohlidal for translation into German and to the graphic designer Jan Havel, who gave the book a unique visual form and shape. As editors, we are very pleased with the prestigious award, as well as the fact that we managed to obtain it with a cultural-historically oriented art book.

Ivo Habán

12/12/2017

12/12/2017Ivo Habán New Realisms of

the Visual Art Scene

in Czechoslovakia

1918–1945

Despite the detailed study of New Objectivity in Germany carried out by European and American scholars over at least the past three decades, there has not been a single attempt to identify and elaborate similar artwork inside Czechoslovakia, including any links to photography, or to consider it in a broader context. This deficit is likely, in part, caused by the stigma carried by realisms from the totalitarian era. Therefore, artwork related to new realisms and created inside Czechoslovakia has been studied within the context of European art merely on a random basis and has not been subjected to any deeper analyses, although in quality it is in every sense comparable to German production.

Focus is on the art of German speaking artists from Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and Slovakia and the progressive interwar realist art of their Czech- , Slovak- and Hungarian-speaking counterparts. Identification of national and regionally specific characteristics and critical terminology is key, as is the abuse of iconographic tropes in propaganda. Art produced in traditional media and photography is analysed, including photography's crucial role brokering modern visual culture and the mass public.

The term Neue Sachlichkeit (‘New Objectivity’) is a broad, umbrella term coined in Germany. It is not commonly used in connection with new realisms emerging in Czechoslovakia at the same time because it carries the stigma of Germanic influence on Czech visual culture. Therefore, we prefer to employ the term ‘new realisms’ which covers all the nuances of understanding the features of inter-war realisms (in terms of both content and form), i.e. of both the right (neoclassicism) and the left (verism) wing as defined in 1925 by Franz Roh in his crucial theoretical work Nach-Expressionismus subtitled Magischer Realismus Probleme der neuesten europäischen Malerei, in which he also discussed in the broader context and definitely not by chance, representatives of Czechoslovakia: Georg Kars, Alfred Justitz and Rudolf Kremlička. Yet the term new realisms is not new at all. One of the advocates of this term during the 1920’s, as opposed to New Objectivity, was for instance Oskar Schürer, a theoretician of German- Czech art and a recognized connoisseur in German speaking art circles in Czechoslovakia. The term new realisms was also favoured by Jean Clair who organized a big international exhibition called Les Réalismes 1919–1939 at the Centre George Pompidou in Paris in 1980.

In Czechoslovakia, manifestations of New Objectivity as a German phenomenon have been associated mostly with German speaking artists often based in areas close to the border – at the periphery of the newly created state. The existing research on this issue in inter-war Czechoslovakia clearly shows the existence of links to New Objectivity in the work of artists from Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia. This issue has most recently been addressed by Anna Habánová in the chapter on New Objectivity in her project Mladí lvi v kleci (Young Lions in a Cage). Impulses of New Objectivity can be also observed in Czech painters, whether in early works of František Muzika, a member of so-called Social Group (Ho–Ho–Ko–Ko), František Foltýn, Svatopluk Máchal, Alfred Justitz, or works of female artists Milada Marešová or Vlasta Vostřebalová-Fischerová. However, the spectrum of modern realisms in Czechoslovakia is much wider and has not yet been interpreted in depth. Other unresolved issues are the existence of parallels between Italian metaphysical painting and magic realism, inspirations by the Novecento movement or the group formed around the Valori plastici magazine, any of which may have also been transmitted indirectly, via Germany and German art. The new realisms do not necessarily stand in sharp contrast to the existing streams of constructivism, poetism and abstraction on the other side, especially when consideration is given to the nonmimetic principles informing the modernist art of that time.

Photography (and its use in design and other areas of mass culture) plays a rather specific role within the context of New Objectivity. After the First World War, it was photography (or more generally speaking, a technical image) as a means of materializing the changing ideas of the new-born society, that was able to represent the new type of clear, communicative, and democratic image that many representatives of the avant-garde were calling for in their longing to distinguish themselves from traditional models of imagery. The key event to help understand the modern concept of photography was the exhibition Film und Foto in Stuttgart in 1929, which introduced a great variety of contemporary photographic methods and had a significant influence on the future of photography and its trends. Inside Czechoslovakia, it was the critical discourse on the nature of photographic imagery in the Fotografický obzor (Photographic Horizon) magazine in the end of the 1920’s, where the main topics were the sharpness and post-production modifications of the positive image. The exhibition in Stuttgart was reflected mainly in the initiative of Alexander Hackenschmied who in 1930 prepared a similar, smaller exhibition of his home photography in Prague’s Aventinum.

The modern scholarly literature uses the term New Objectivity in connection with certain photographs (Josef Sudek – advertising photography, Jaromír Funke – his Kolín based works, Jaroslav Rössler – cycles made in the 1930’s, and the works of Eugen Wiškovský), but fails to delve any deeper into analysis of the term itself and the relevance of its use within this context. While it has been given some marginal attention in several theses, the relation between New Objectivity and photography in Czechoslovakia has not yet been the subject of any independent study. In the context of this project, the research focuses on the reflection of New Objectivity in the Czech and Czech-German context (professional photographers, but also the activities of amateur associations in which German-speaking artists had close links to what was happening in Germany), as well as the question of to what extent the term New Objectivity can be used in connection with photography, and by extension, what links there are between New Objectivity and all new visual media.

The study of terminology will develop precise elaborations of the key terms New Objectivity, magic realism, imaginative art, metaphysical painting, neoclassicism, verism, social art, civilism, and primitivism. The project will expand existing research and further develop the understanding and interpretation of the topic based upon knowledge of German artists inside Czechoslovakia and the most recent scholarship about the Czech art scene. While independent research projects on New Objectivity, clearly defined in terms of territory, have been carried out by teams of scholars on a European scale, an urgent need arises to study the situation at the very heart of Europe to fairly evaluate the key role of the Czechoslovak art scene which culminated in a range of open, multifaceted attitudes and artistic views between 1933 and 1938. But it also paved the way among the so-called Czech Germans for the onset of pro-Hitler oriented naturalism and related propaganda.

This will not be an imaginary confrontation between the Czech- and German-speaking spectrum of the inter-war art scene in Czechoslovakia conducted on a formal basis. Instead, the artwork that falls within the scope of the project will be analyzed in ways to supplement and partially revoke the persisting traditional perception of modern trends in the history of art concerning inter-war Czechoslovakia by taking into account its formal, national and gendered aspects. So far, this art historical lens has been primarily used to view the work of Czech-speaking modern artists defining the national style of the newly created state, and the Francophile avant-garde; and it has not taken into account other progressive realistic trends which developed in parallel after the decline of expressionism, trends often linked to the German-speaking art scene.

© Ivo Habán, 2017